North Central Division Project Spotlight: Fisheries Scientists Take Multi-Faceted Approach to Managing Common Carp in Iowa’s Shallow, Natural Lakes

By Ben Wallace, FMS North Central Division Representative and Fisheries Management Biologist with the Iowa Department of Natural Resources

Iowa’s glacially formed lakes are among the most nutrient rich aquatic ecosystems in the world. While land use practices in the watershed play a big role in this, oftentimes a large portion of the nutrient loading can come from within the lake itself. The culprit in many of these cases are the Common Carp Cyprinus carpio. Introduced into Iowa in the late 1800s, the fish are ubiquitous throughout the state and are a major problem when it comes to managing water quality and fisheries. They create turbid conditions by destroying aquatic vegetation and resuspending lake bottom sediments through their feeding activity. They thrive in the conditions they create and other native species soon begin to suffer.

Iowa has a long history of trying different methods of managing Common Carp populations. Various commercial fishing programs, chemical renovations of lakes using rotenone, and fish barriers have all been used over the decades. As time goes on and fishery managers learn more about the species and how they interact with their environment, some of these practices come full circle. The Spirit Lake Fish Management crew and Natural Lakes Research team, led by Mike Hawkins and Jonathan Meerbeek, respectively, set out to create a formula for success by combining some of those past management strategies in just the right way.

Commercial fishing can lead to large hauls of fish and mass removal from a system, but how many need to be removed to make a noticeable difference in water quality? How do you keep commercial anglers fishing when they start to experience diminished returns that eat into profits? And, if you remove enough fish to make a difference, how do you keep the standing stock low for an extended amount of time? To solve this issue, Mike and Jonathan took everything they knew that did not work, what did work, and combined it with recent Common Carp research across the Midwest and focused on Lost Island Lake. A roughly 1,000-acre glaciated lake with a complex system of wetlands attached to it.

The plan was to install fish barriers in every single location where Common Carp could enter a wetland, their prime spawning habitat. The idea was to force the Common Carp in Lost Island Lake to spawn in the main lake basin, where in theory, they would be less successful. Once the barriers were built, the Common Carp would be eradicated from the wetlands by either a drawdown or rotenone depending on what the situation called for. At the same time, the standing stock in Lost Island Lake would be reduced to less than 50 pounds per acre. As the standing stock is reduced, the lake would be stocked with a diverse assemblage of native predators, such as Largemouth Bass Micropterus salmoides, Walleye Sander vitreus, and Northern Pike Esox lucius.

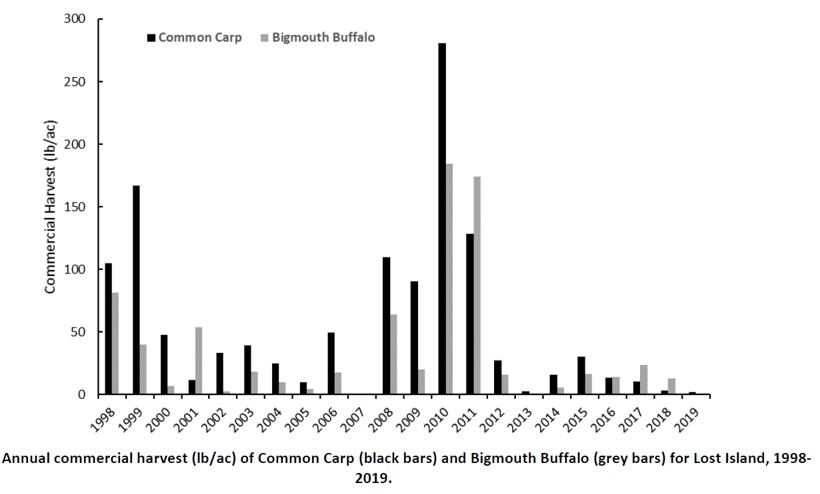

Fish barrier construction began in 2010 and was finished in 2011. Four barriers were constructed to effectively block access to all of the wetlands associated with Lost Island Lake, thereby reducing the reproductive potential of Common Carp. Concurrently, an incentivized commercial fishing contract to remove Common Carp was awarded and removal efforts began (Photo 1). Bigmouth Buffalo Ictiobus cyprinellus were also allowed to be harvested, but removal of this species was not incentivized. In the first year of the incentivized contract, a total of 891,900 pounds of Common Carp and Bigmouth Buffalo were harvested (Figure 1). This equated to 743 pounds of fish per acre removed from the system. By the second year, removal totals had exceeded 1.43 million pounds of fish. In the subsequent years commercial fishing continued, although it was not incentivized and harvest dropped dramatically, but so did the standing stock.

Photo 1. Sorting fish following a seine haul under the ice at Lost Island Lake.

Figure 1. Commercial harvest of rough fish from Lost Island Lake 1998-2019.

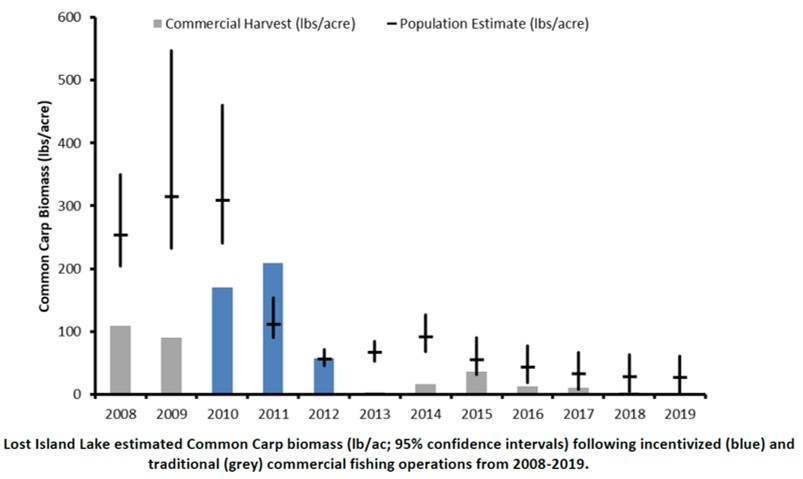

By 2012, Secchi depth began to increase, turbidity levels dropped, aquatic macrophyte abundance and diversity increased, and Centrarchid populations exploded. Other species, like Yellow Perch Perca flavescens, were taking advantage of the improved water clarity and macrophytes and their numbers started to grow. Ten years out Lost Island Lake is still experiencing the benefits of that effort. Common Carp densities remain below 50 pounds per acre (Figure 2) and sport fish populations are still flourishing. This project has served as a great example of how a multi-pronged approach can address the Common Carp and water quality problem plaguing Midwestern shallow lakes. This approach is being replicated across more systems in Iowa. Some have been successful, others have struggled to get commercial fishing to remove target quantities. Each effort teaches us more and helps to refine the recipe for success. One thing that shouldn’t surprise anyone, is that a full understanding of the entire fish population, water quality issues, watershed, and wetland connectivity is essential to managing these lake systems.

To read the full report on the Lost Island Lake project click here.

Figure 2. Common Carp standing stock in Lost Island Lake 2008-2019.